30 de November de 2020

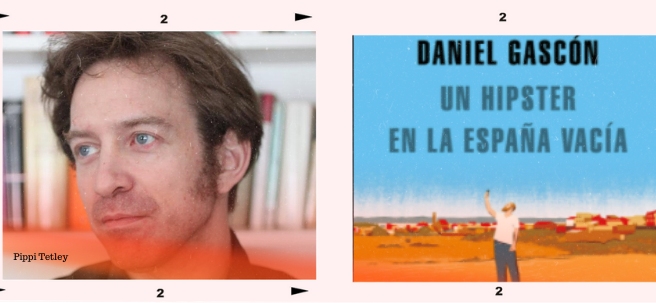

November 26, 2020. Daniel Gascón (Zaragoza, 1981) is a writer and editor of the magazine Letras Libres, as well as a columnist for the newspaper El País. This pandemic summer, he published the novel "A Hipster in Empty Spain," in which Enrique Notivo, the main character, decides to move away from the big city to live in his grandmother's village in Teruel. The novel is a satire in which the protagonist tries to adapt, with his best intentions and urban prejudices, to the rural life he has chosen, and in which he tries to grow a collaborative garden.

- Daniel Gascón – author of the book “A Hipster in Empty Spain” – speaks with the National Rural Network about the satire he has captured in his novel about the arrival of “neo-rurals” to the villages.

|

National Rural Network: Do you think there's a growing interest in "rural literature" or is it just a fad?

Daniel Gascón : It's always been a recurring theme in our country. Many writers write and have written about rural Spain from many different perspectives and points of view. Rural life is part of our lives and our reality, and there are periods when it receives more attention, and times when it receives less. Right now, it's receiving more attention. But rural Spain is like the Guadiana River: it appears and disappears, but it's always there.

RRN: How and why did “A Hipster in Empty Spain” come about?

DG: It arises from the confrontation or differences I see between my hipster friends in the city—and their romantic vision of the countryside—and the reality I've experienced since I was a child in a rural setting. It's this contrast that led me to express it in an ironic and sarcastic way, in the form of a humorous novel.

RRN: You mentioned growing up in a rural area. What was your life like in rural areas from a young age?

DG: My mother was a rural family doctor and primary care physician, and until she got a permanent position, we traveled around towns every summer until I was 10. From that age on, we settled in Urrea de Gaen and Iglesuela del Cid (Aragón), and when I went to high school, since there weren't any, I moved to live with my grandparents in Zaragoza, who had also emigrated to the city from the mining areas. Because of all this, my education was in rural schools . In my generation, if your parents weren't from the countryside, your grandparents were.

RRN: Explain the title: why a hipster to symbolize the city and why the term “empty Spain” to refer to the rural environment?

DG: In the title, I wanted to capture the contrast I'm talking about and make clear from the start that dialectic between the rural and urban worlds. For me, a hipster is a sophisticated guy who's up to date and, on top of that, is concerned that everyone knows he's in fashion. And with "Empty Spain," I wanted to use a term that's very graphic and descriptive but has very different connotations than "Empty Spain." With "Empty Spain," we're saying that the interior of the country has lost population due to various factors. Many of them for completely natural and logical reasons. However, with "Empty Spain," it's as if someone has kicked people out, and that's not the case. It's not about finding someone to blame or someone responsible. It's a phenomenon of multiple nature, but often gradual and natural over time.

Also, I wanted to come up with a funny, incongruous title that you would know from the start was for humor and not drama, something like “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” by Mark Twain.

RRN: What are your thoughts on rural development based on the research you've done for this work and your own experiences?

DG: For me, rural development means trying to ensure that primary sector towns acquire a socioeconomic model that allows them to continue developing independently. The most complicated part is how and what measures to implement. But it's important for provinces to maintain a network of towns with a settled population for the development of the province as a whole. Globalization and digitalization have largely equalized urban and rural areas, however.

RRN: What do you think of the so-called “neo-rural” movement?

DG: The longing to return to the countryside has always been present. Besides, life in the villages is much more comfortable now than it was 30 years ago, when there wasn't even electricity. For this phenomenon to take hold, it's essential that information reach all areas equally. From my experience, I know that if you arrive in a town with humility, without posturing or idealization, it's much easier to get used to it. Of course, you must be willing to lose your anonymity—an intrinsically urban quality—and forget about the exhibitionism of cities. Which is precisely what I parody in the book.

RRN: Do you think the pandemic marks a before and after between rural and urban areas?

DG: The pandemic has made cities lose all their appeal. Without cultural offerings, with the threat of the virus on public transport, and confined to small, expensive spaces, it's inevitable to fantasize about leaving. This is something we've all fallen into. And some are even taking the plunge. In fact, there are people who didn't think they could adapt to rural areas and are taking the plunge. It remains to be seen whether this migration will be massive or not. There are many factors to consider when making this decision: your job, your children's education, if you have any, and so on.